In the face of new inside and outside threats, intensive discussions are currently underway regarding the future of the European Union. The increasing pressure to reform should be used to substantially reorganize the EU budget. The recent proposals of the European Commission for the next Multiannual Financial Framework (MFF) still lack ambition in this respect.

European Union: New priorities for the EU

The list of new challenges and tasks for the EU is extensive: the upcoming Brexit, the refugee crisis, terrorist attacks, the erosion of democratic structures and populist EU criticism in several member states, the protectionist policies of the US administration and the aggressive demeanour of Russia, China and Turkey - in the face of these troubled waters, the EU must demonstrate its capacity to act and set new priorities.

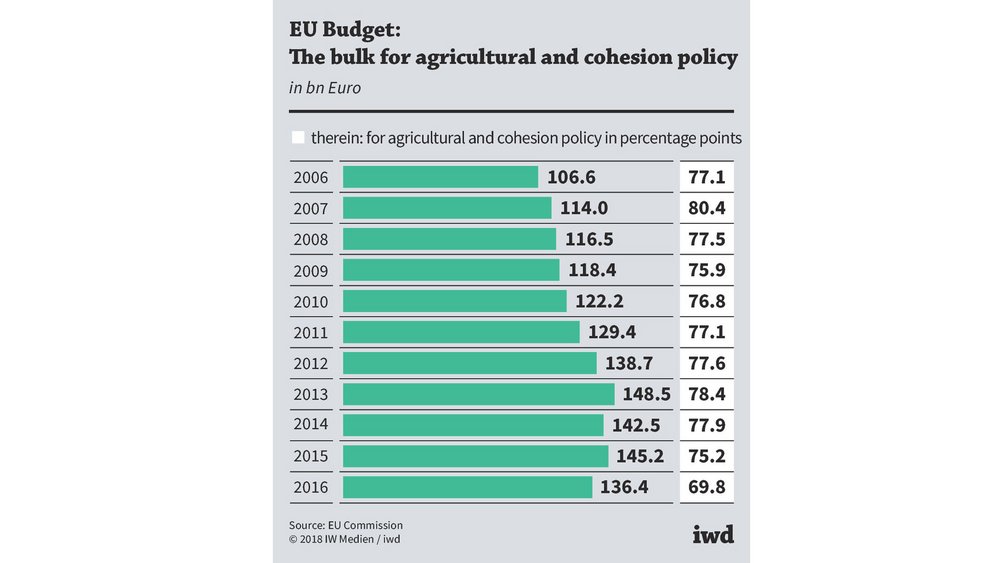

A look at current past EU budgets shows that most of the spending still falls on two areas (chart 2):

Between 2006 and 2016, spending on agricultural and structural policies totalled around 70 to 80 percent of the EU budget.

This high proportion is anachronistic, especially as far as agricultural expenditure is concerned. The share of agriculture, forestry and fisheries in total gross value added at the beginning of the current MFF in 2014 was only 1.6% on the EU-28 average.

In February 2018, the European Commission proposed a menu of potential additional spending priorities for the EU. These include (apart from a funding gap of around € 73 billion from the UK's exit from the EU) € 40 to € 80 billion to boost research and development and up to € 146 billion to secure the EU's external borders.

Restructuring the budget without increasing it. However, the growing need for funding encounters resistance: a number of EU countries are strongly opposed to an increase in the EU budget, and some are even calling for a cutback because of Brexit. Indeed, a significant expenditure shift could easily avoid a budget increase. Such a shift also encounters strong opposition of the beneficiaries of agricultural subsidies and cohesion spending.

However, the EU Commission must not be deterred by the usual political resistance, but should show strong determination and use the changed geopolitical situation to finally put the financial framework on an economically sounder basis.

The German Economic Institute calculated how this could be achieved: Accordingly, new priority tasks of the EU could be financed without expanding the budgetary framework or opening up new sources of finance - only through shifts in the budget.

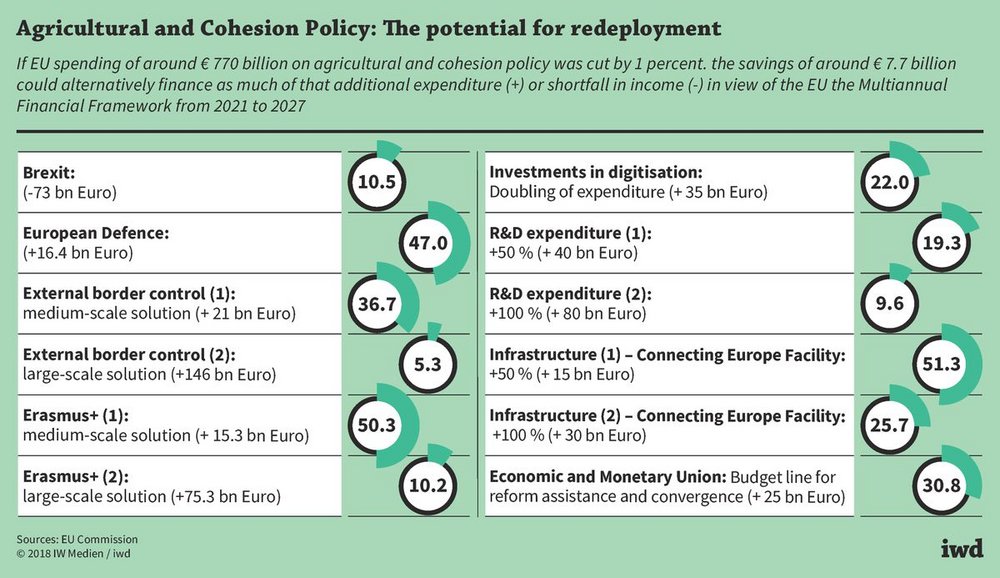

Reductions of agricultural and cohesion expenditure offer large levers. In the current MFF for 2014-2020, spending on agricultural policy adds up to around € 400 billion and cohesion policy expenditure to around € 370 billion (according to the European Commission). If these 770 billion euros were cut by only 1 percent, around 7.7 billion euros would be available for other purposes (chart 1): For example, nearly 11 percent of the shortfall by Brexit could be funded with the money.

With a 2 per cent reduction in agriculture and cohesion expenditure the Erasmus+ programme could be doubled, the spending on cross-border infrastructure could be increased by a half or, alternatively, the additional defence spending, proposed by the European Commission, could be fully funded.

If so much can achieved by only small reductions, another step is near at hand:

Full financing of additional priority expenses possible by mere restructuring. If one sets only the medium-scale version for the new expenditure priorities, the EU needs around 240 billion euros for the complete financing of all additional expenditures – i.e. if for R&D funding additional needs of 40 (medium-scale solution) instead of 80 billion euro (large-scale solution) was chosen (see chart 1). This amount could be raised if the 770 billion euro for agricultural and cohesion policy were cut by 31 percent.

Savings on this scale are reasonable due to the lack of economic arguments for agricultural subsidies. Reduction of this size are also quite feasible in cohesion policy, In line with the subsidiarity principle, the EU should only concentrate on poor regions in need of commonly financed support, while the wealthier Member States should pay for regional support themselves. Instead, the EU Commission intends to still include all regions in its new MFF proposals for cohesion policy.

The savings needs are considerably smaller in a dynamic perspective when economic growth is taken into account. The size of the EU budget is related to the combined gross national income (GNI) of the member states, so that financial leeway grows in line with nominal economic growth.

Based on extended forecasts of the EU Commission and the International Monetary Fund, the GNI of the member states can be assumed to increase by a more than 28 percent by the end of the multiannual financial framework from 2021 to 2027. According to the current budgetary logic, agricultural and cohesion expenditure would then increase by 220 to just under 990 billion euros - and the need for cuts from 240 to almost 310 billion euros. But:

If EU spending on agricultural and cohesion policy were frozen at the current level, economic growth would create a buffer of € 220 billion that could be used for financing the new priorities.

The need to reduce agricultural and cohesion policy would thus decrease from € 310 billion in the future to just € 90 billion. This is just under 12 percent of the current 770 billion euros - instead of 31 percent.

The European Commission proposes to cut cohesion spending only by 7 percent according to expert estimates. This is a step in the right direction, but does not go far enough.

Berthold Busch / Jürgen Matthes: On the Future of the European Union

IW-Policy Paper

Berliner Gespräche Frühjahrstagung: Zwischen Sicherheitspolitik, Green Deal und Wettbewerbsfähigkeit – eine europapolitische Bestandsaufnahme

Das Institut der deutschen Wirtschaft möchte Sie erneut zu einer virtuellen Variante der „Berliner Gespräche” einladen.

IW

Die Zukunft Europas: Welche Prioritäten sind für die Wettbewerbsfähigkeit entscheidend?

Die Europäische Union hat ihre neue strategische Agenda für die Jahre 2024 bis 2029 veröffentlicht. IW-Direktor Michael Hüther und HRI-Präsident Bert Rürup analysieren im Handelsblatt-Podcast „Economic Challenges” die Bedeutung der Wettbewerbsfähigkeit für die ...

IW