Putin's war in Ukraine has been going on for over a week now. In order to hit Russia hard financially, an import stop for gas is also discussed. This would not only put a strain on Russia, but also on the European gas supply.

Russian gas: Can Europe cope with an import stop?

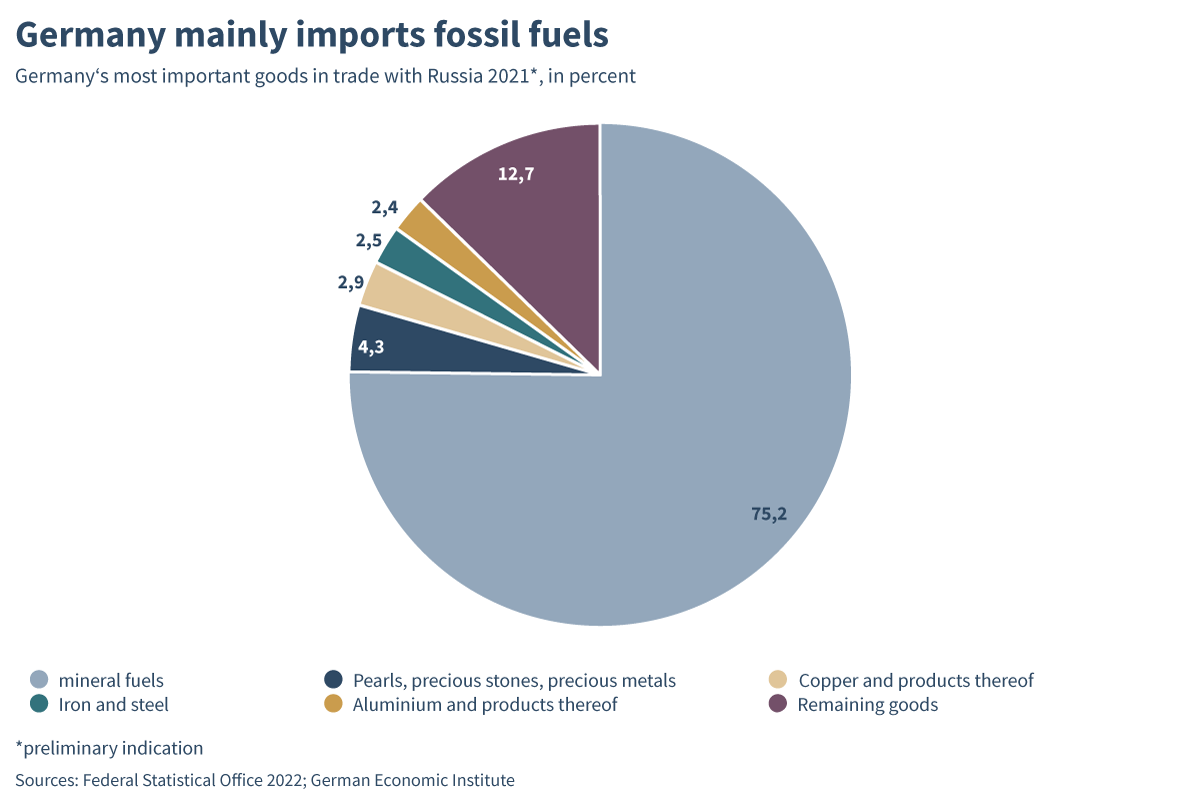

Natural gas has an important role in Germany's energy supply: around 75 percent of Germany's imports from Russia are mineral fuels, which include gas (Figure 1). We cover more than half of our import needs through Russian supplies. Other countries in Europe are also heavily dependent on Russian gas supplies; Italy, for example, imports similar proportions of Russian gas - for some states in Eastern Europe, such as Finland or Bulgaria, the figure is even higher.

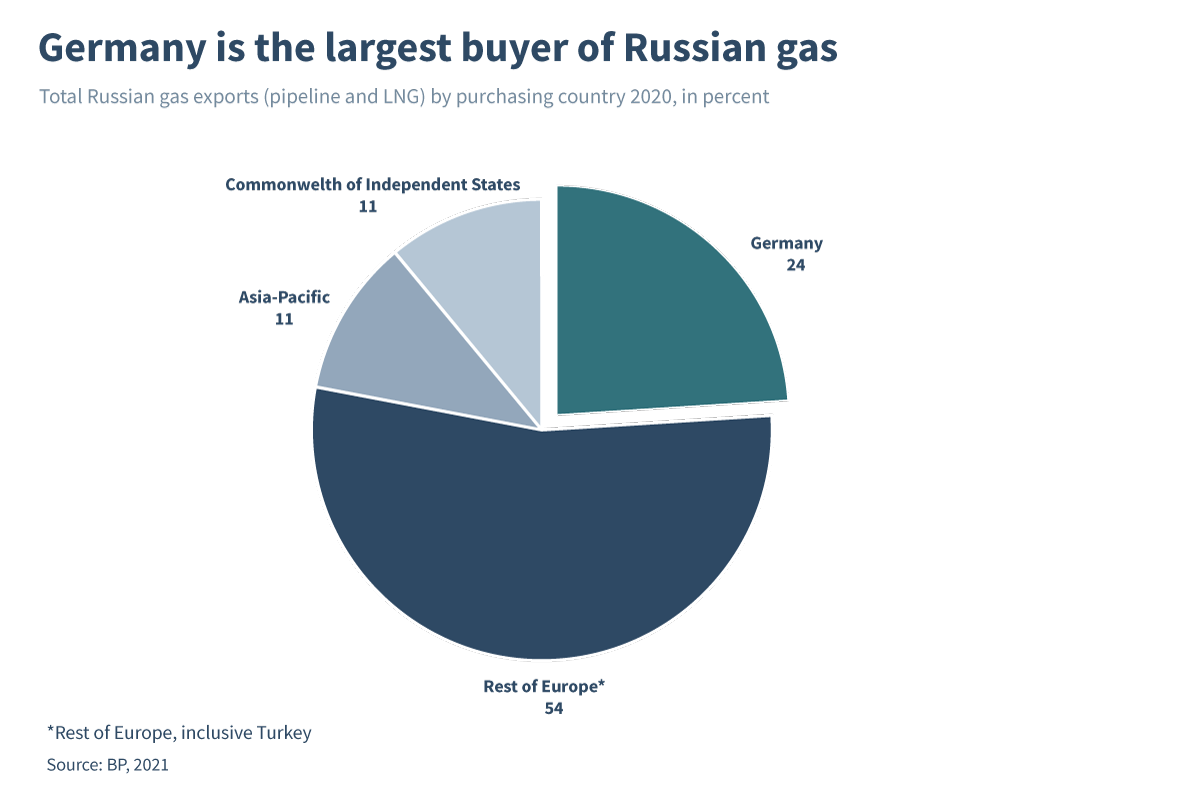

The dependance exists on both sides: Fossil raw materials are the central source of income for Russia, and the country is one of the world's largest exporters of gas, oil and hard coal. Around three quarters of gas exports go to the European continent - the Federal Republic of Germany is Russia's most important customer with almost 25 percent (Figure 2). In order to further tighten the sanctions against Putin, an import ban on the part of the EU members is therefore also being discussed; this step would hit Russia hard. But what would happen to supply security in Europe?

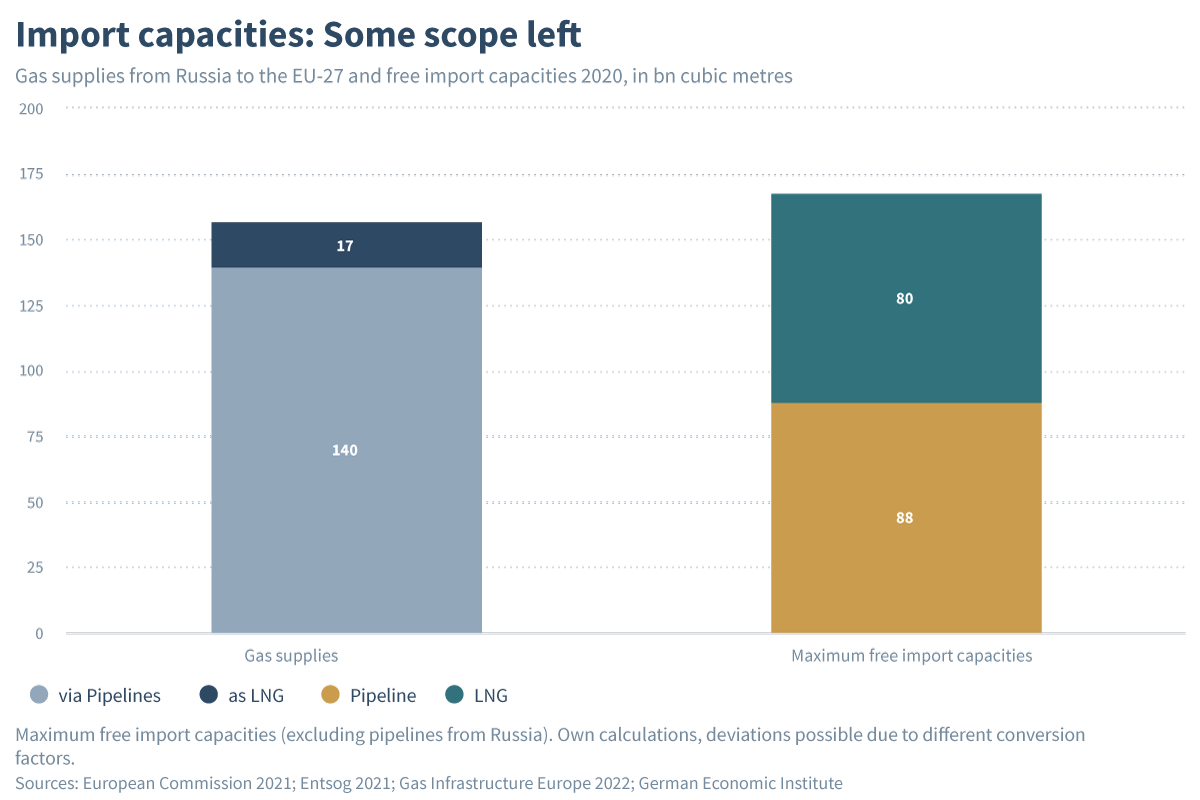

Most of the gas is transported to Europe via pipelines, not only from Russia but also from Norway, Algeria and Azerbaijan. Liquefied natural gas (LNG), which is imported by ship and converted back into gas form at designated terminals, has become more important in recent years. In 2020, LNG accounted for 26 per cent of European imports. If the EU now boycotts Russian deliveries, Europe would have to purchase much larger quantities of the liquid gas. In theory, the free pipeline and LNG capacities in 2020 would have been sufficient to compensate for the Russian gas (Figure 3). But the problem is in the details: it is unclear, for example, whether the countries connected via pipelines, such as Norway and Algeria, and the exporters of LNG, such as Qatar, Australia or the USA, would be able to supply the required quantities. The location of the European LNG terminals also complicates the project.

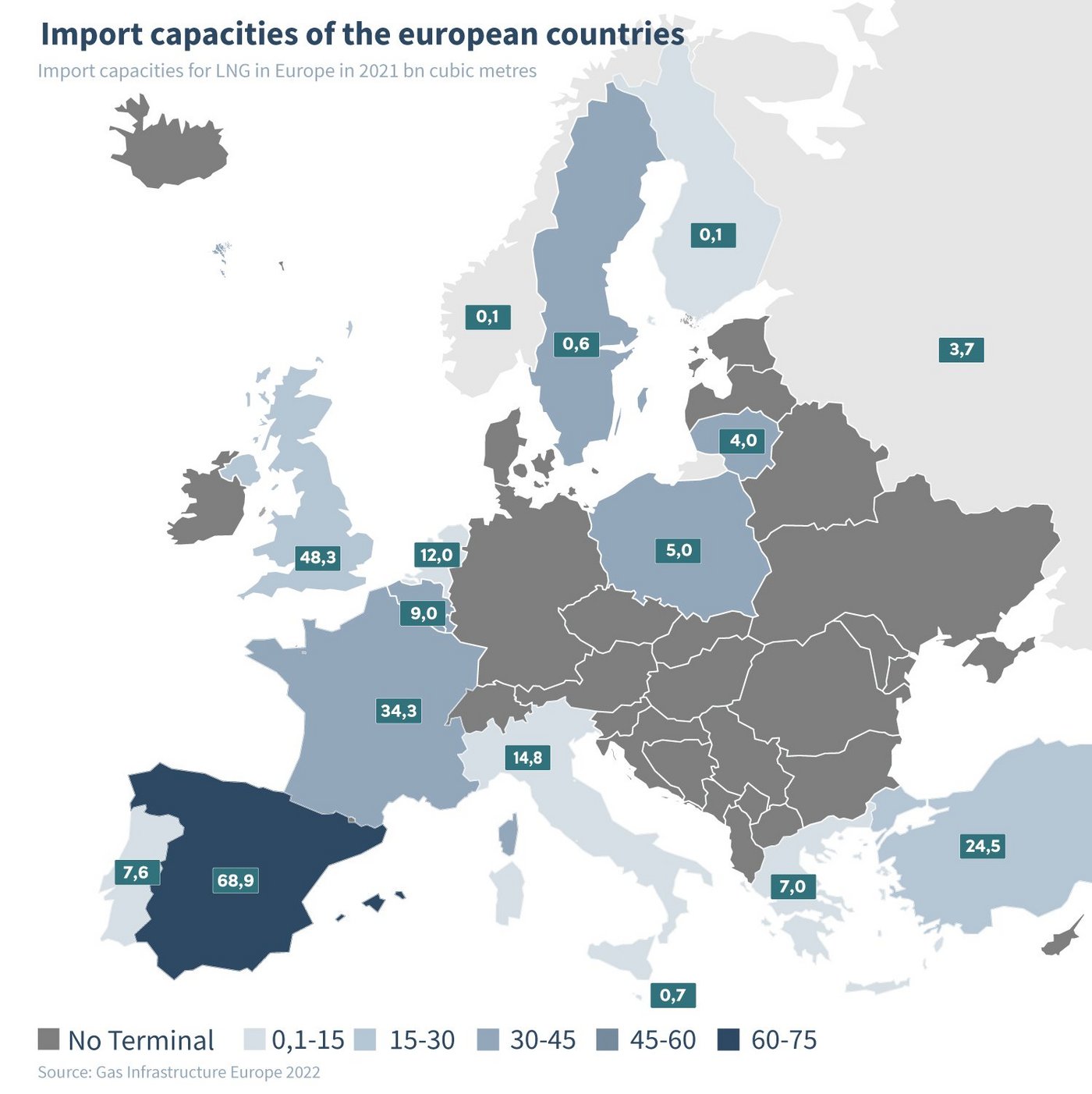

Spain has the largest capacity for LNG - together with France, the two countries account for 60 percent of total European capacity. But there is a lack of infrastructure to transport the gas in larger quantities to other EU member states. Southeast Europe in particular lacks its own LNG terminals, storage facilities and transport options to replace Russian gas supplies (Figure 4). This is where an import stop would be felt first.

Estimates suggest that current European LNG capacities could cover around 40 percent of gas demand. If all announced LNG projects or those under construction were realised, up to 65 percent could be served. In Germany, for example, two terminals are to be built in Brunsbüttel and Wilhelmshaven, and a further terminal in Stade is still being discussed. However, these values only refer to the maximum import capacity of the EU. Due to the limitations of the transport infrastructure, further distribution is not easily possible on this scale.

In the short term, Europe could only insufficiently compensate for an import stop. But a rapid expansion of the LNG terminals will reduce dependence on Russia at least in the medium to long term. Because the terminals are also suitable for hydrogen imports, they could even become an important component of the energy transition. In the long term, the decisive lever for independence from Russian gas imports lies in the expansion of renewable energies.

More on the topic

Financing the Sustainability Agenda

The EU has set legally binding targets for climate-neutrality by 2050. To succeed in the transition to a low-carbon economy, companies need to continuously develop new and improved climate-friendly technologies, and to adopt or move towards low-carbon business ...

IW

Is the EU Fit for 55 and Beyond?

Ursula von der Leyen was elected President of the European Commission by the European Parliament in July 2019. She assumed office in November 2019 and unveiled the European Green Deal in December 2019 (European Commission, 2023a) as a focal point of European ...

IW