On 23 June, the UK will hold a referendum on whether the country will remain in the European Union. If the vote falls in favour of the Brexit, the British government will have to restructure its cooperation with the EU on the political and economic levels. Proponents of leaving the EU are hoping for a tailored agreement for the United Kingdom. However, this isn’t very realistic.

Brexit: Cherry picking is just wishful thinking

Will 2016 prove to be a fateful year for the European Union? If the majority of British voters in the referendum say “no” to EU membership, it would be the first time a country has actually left the European Community. The exit would take place once the terms and the framework of future relationships are outlined in an agreement – at the latest, two years after London announces the exit. This period of time could only be extended if both sides agree.

Those in favour of the Brexit are wagering on the negotiation of an agreement with the EU – an agreement fully aligned with the UK’s terms. Specifically:

Continued access to the Single Market. Brexit proponents don’t want to shake up the possibility of continuing to offer their goods and services in the EU, but they no longer want the UK to take part in the EU’s common agricultural policy or regional policy.

More freedom. The Brexit supporters want to rid themselves of the EU regulations they consider burdensome and to shape their economic relations with countries outside the EU as they see fit.

Financial relief. Of course, EU critics also prefer to spare the UK from contributing its part to the EU budget. Between the years 2010 and 2014, this contribution amounted to 8.5 billion euros net, on average – that is, a good 0.4 per cent of the British GDP.

An end to free movement. One of the central arguments of Brexit supporters is that Britain could once again set its own terms for EU citizens wishing to reside in the UK.

However, an agreement that meets all these requests – essentially allowing London to pick the proverbial cherries out of the EU’s cake – surely wouldn’t stand much of a chance in Brussels. After all, the EU will certainly do all it can to make sure the exit has painful consequences for the British – at the very least to scare off anyone who might consider following the UK’s example, and to prevent the gradual disintegration of the European Community.

Against this backdrop, the participants can expect a long and drawn-out struggle for a consensus. The trade agreements that the EU reached with non-EU countries provide a hint of how long such negotiations might take: it took the countries between four and nine years to reach the respective agreements.

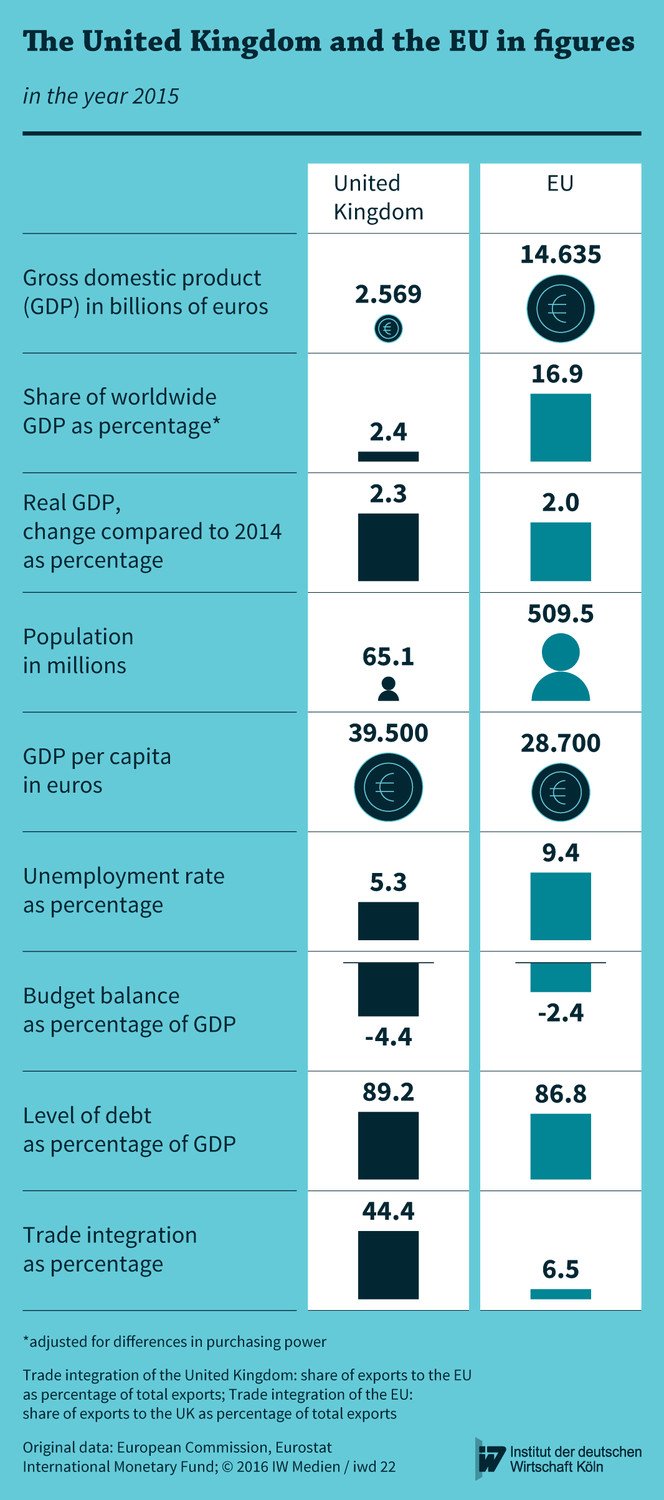

The question of which negotiating partner is able to assert its demands, and to what extent, also depends on the particular country’s market power. And the UK doesn’t have the strongest cards when it comes to this point (see chart).

In the year 2015, the United Kingdom delivered a good 44 per cent of its exports to other EU countries – while only 6.5 per cent of EU exports went to the British Isles.

Thus, the EU is considerably less dependent on access to the British market than the other way around.

Another indication that the negotiations could be lengthy is the fact that, depending on the configuration of the exit agreement, it might have to be ratified by all EU countries; in other words, the qualified majority within the Council of the EU might not be sufficient.

However, if the British leave the European family, they will not only have to realign their relationship with the EU, but also renegotiate over 30 trade agreements with more than 50 non-EU countries, such as Mexico, South Africa and South Korea. The UK would also have to enter into new negotiations with the United States in place of the TTIP. Since each step of the agreement process requires great effort, it will take a very long time to get all new agreements finalised. Moreover, these countries will likely be more reserved about making new concessions, considering that the UK is a smaller and thus weaker partner in comparison to the EU.

After adjustment to reflect differences in spending power, the EU-28 generates nearly 17 per cent of worldwide GDP – while the UK alone makes up a share of only 2.4 per cent.

On the one hand, an exit would enable the British to do away with the tariffs previously imposed in connection with EU agricultural policy as well as other trade barriers. On the other hand, they would no longer have an ace up their sleeve in future negotiations with non-EU countries. After all, why would these countries make any further concessions towards the UK if they already have free access to the British market?

All of this seems to indicate that the Brexit proponents have miscalculated and that the UK will end up on the losing end of the deal. But the question remains as to how strongly the Brexit would impact the British economy. There are several studies in which the UK has gotten off relatively easy – with the long-term estimated costs of an EU exit ranging from 1 to under 5 per cent of the British GDP.

However, the analyses do not give sufficient consideration to the advantages of the UK’s economic interlocking with the EU. For instance, they mostly overlook the positive impact resulting from the fact that European integration not only leads to increased trade but also to an increased stream of direct investments. This raises the level of competition, in turn resulting in more innovations and a more efficient use of resources such as labour and capital.

Hence, it is plausible that the Brexit could have very grave consequences. Britain’s treasury, for example, estimates that a real shock could come within as little as two years:

On the short term, the Brexit would cost the British economy up to 6 per cent of the GDP and cause the number of unemployed individuals to increase as high as 820,000.

Another study on the part of the British treasury bases its assessment on a worst-case scenario, by which the British GDP over the long term – that is, after 15 years – would be 9.5 per cent lower than if the country remained in the EU. In absolute terms, this would cause each British household to lose around 6,600 pounds per year (1 British pound currently corresponds to approximately 1.30 euros).

One might argue that the government in London is deliberately floating these negative figures in an effort to deter Brexit supporters. Yet the figures appear to be realistic. Indeed, the OECD puts forward similar statistics; in its pessimistic scenario, it shows the Brexit would impact the British GDP by a negative 7.7 per cent, thus amounting to a financial loss of 5,000 pounds per household.

More on the topic

China’s Trade Surplus – Implications for the World and for Europe

China’s merchandise trade surplus has reached an all-time high and is likely to rise further. A key driver appears to be a policy push to further bolster Chinese domestic manufacturing production, implying the danger of significant overcapacities.

IW

What if Trump is re-elected?

A possible re-election of Donald Trump as US president in November 2024 could entail a significant upheaval for the world trading order, if he fulfills his announcements to raise tariffs, mainly in order to reduce the US trade deficit.

IW