For decades now the EU has constantly been broadening its policy to promote economic and social cohesion. But all spending is now under scrutiny, and not only because they are about to lose a key net contributor in the form of the UK. A recent IW study reveals that more than EUR 20 billion could be saved every year if the cohesion funding were only granted to economically weaker Member States.

EU Cohesion Policy: Focusing on what is important

Europe is genuinely facing a myriad of challenges at the minute. The EU has to help combat the causes of migration in order to prevent new refugee crises. At the same time, borders have to be secured and terrorism defeated. This all costs a lot of money. Furthermore, it looks very likely that Brexit is just round the corner – according to information from European Commissioner for Budget and Human Resources Günther Oettinger, this will hit the EU to the tune of more than EUR 10 billion per year from 2020. The higher spending and the missing revenues collectively threaten to create a hole in the budget of up to EUR 30 billion per year.

This is why the EU is urgently scrutinising its current spending, and this applies in particular to the so-called cohesion policy. The policy is based on a contractual obligation to promote economic, social and territorial cohesion within the EU. Special emphasis is placed on reducing developmental differences between regions, and helping particularly disadvantaged areas catch up.

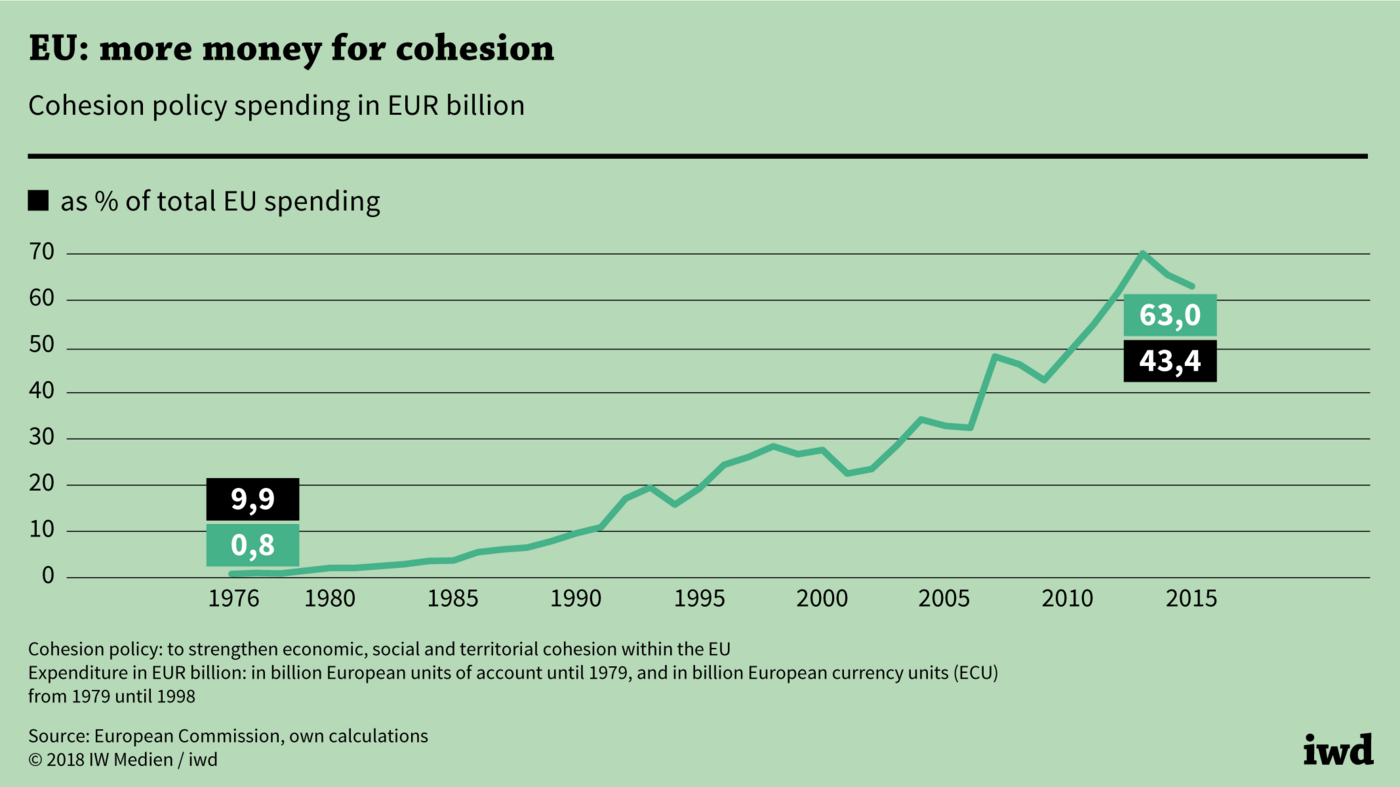

To achieve these goals the EU has invested increasing sums of money over the years (see figure):

Annual cohesion policy spending has risen from roughly EUR 1 billion at the end of the 1970s to well in excess of EUR 60 billion today.

This means that almost one in every two euros that the EU spends is channelled into cohesion policy measures – including the agricultural structures policy.

Glancing at the details quickly reveals that the funds are often set up or replenished in connection with expanding or deepening the EU – almost as part of political deals. What is more, since 2007 cohesion policy has also been designed to help Member States reach the growth and employment objectives set by the EU.

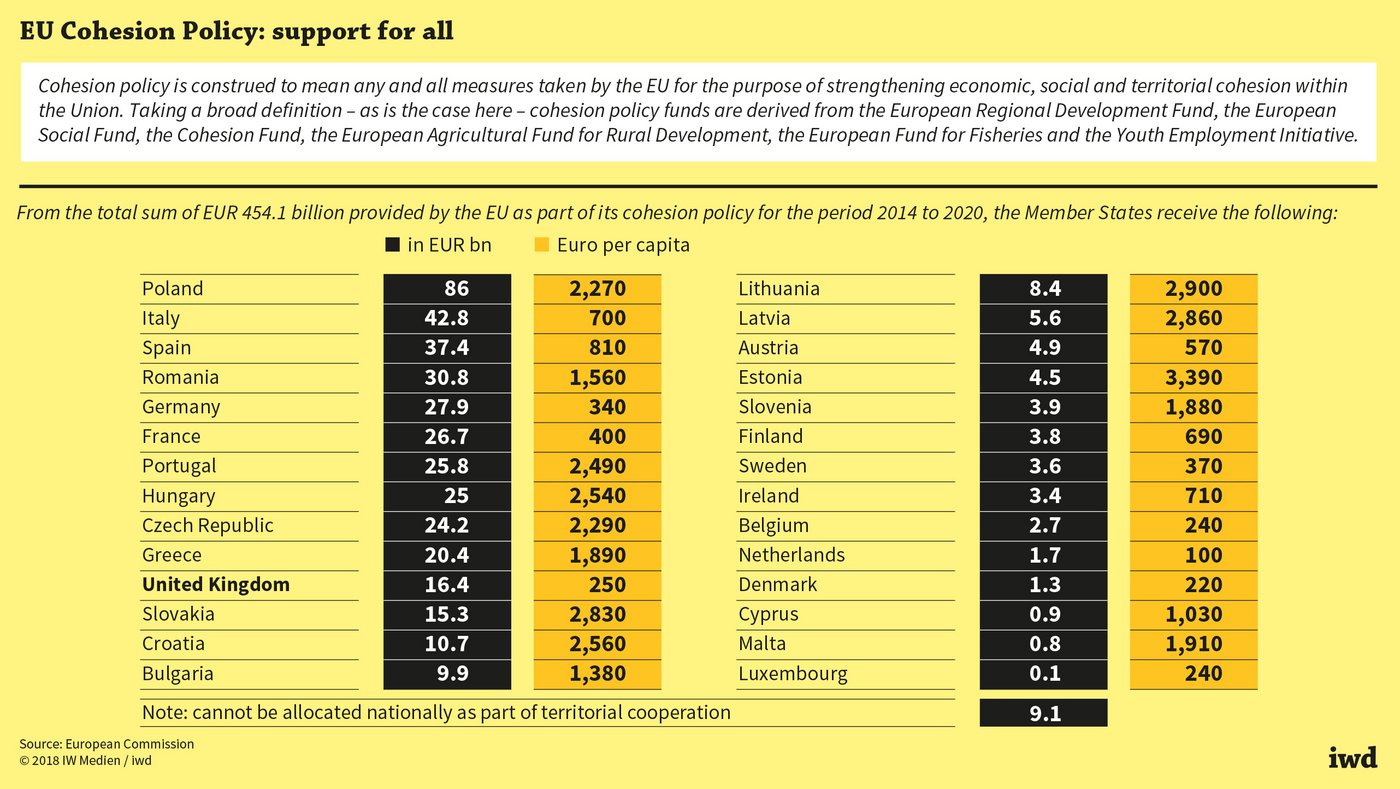

However, this means that in principle, every region in the EU can hope to receive a slice of the cohesion fund pie. In the current funding period, no country has gone empty handed (figure):

In the period from 2014 to 2020, all 28 EU Member States have benefited from cohesion funds amounting to more than EUR 454 billion.

Even the rich country of Luxembourg received over EUR 100 million. In absolute terms, most of the money is channelled into Poland; but per capita, Estonia comes out on top.

So cohesion policy is extending far beyond its original objective of supporting particularly the poorer Member States and regions. Taken together with the looming gaps in the budget, these are all good reasons to re-focus cohesion policy on what is most important. The German Economic Institute (IW) has presented a model calculation for this that is based on inflows and outflows of cohesion policy funding from 2011 to 2015.

Looking at the average over these years, EU Member States (without Croatia) spent a good EUR 50 billion on cohesion policy. If we net the contributions imputed fictitiously to the individual countries with the funding received, there were 15 net beneficiaries receiving a total of EUR 27.8 billion per year. In other words:

With a figure of EUR 22.4 billion on average over the years 2011 to 2015, almost half of all cohesion funding did not go to the poorer states, and was simply redistributed between the wealthier and the poorer groups of Member States.

The IW model calculation assumes that the contributions made by the United Kingdom will disappear as a result of Brexit. What is more, the cohesion funding should only be financed by the more prosperous states in the future – i.e. by the net payers so far – and given to the poorer countries. According to this reform proposal, for example, Germany would no longer pay EUR 10.4 billion per year and receive almost EUR 3.6 billion, but would only make a contribution of around EUR 8 billion. By contrast, Spain, who previously paid EUR 4.2 billion but received EUR 5.3 billion, would become a net recipient of cohesion funds amounting to more than EUR 700 million.

All in all, the volume of cohesion policy funding could be reduced from more than EUR 50 billion to less than EUR 27 billion – without the poorer Member States being forced to suffer any losses.

The countries that are economically stronger would no longer receive money from Brussels for their regional and structural policies, and would primarily be responsible for this themselves. The EU could support the poorer regions of these countries with loans, guarantees and similar financial instruments.

More on the topic

Current account: Surplus is no ground for sanctions

The German economy is operating profitably in foreign trade. But contrary to popular belief, the current account surplus does not adversely affect the European countries impacted by the financial crisis. Indeed, the economic ascent of the newly industrialised ...

IW

German Energy turn-around – Energiewende: Electricity looking for storage

Battery storage could go mainstream with growing shares of power produced from wind and sun and electric cars becoming more common in the streets. A rapid growth of the role of rechargeable batteries would, however, also lead to a significantly higher demand ...

IW