The British are expected to vote on their EU membership in 2016. If they decide to withdraw, this will present challenges in various areas, including the UK’s free movement of goods and services with the EU countries. British financial and corporate service providers in particular will have new trade hurdles to face, but so will the chemical and power industries.

British gambling with high stakes

They never wanted the euro, they do not like handing over power to Brussels, and they are taking their own approach to the current refugee crisis. The British seem to have trouble finding any common ground with “the Continent.” The United Kingdom may well have been a member of the European Union since 1973, but for the British, being part of the EU family was never really a matter of the heart. For years, Eurobarometer survey results have shown that a majority of British citizens have a negative view of the EU – while other member states have a notably better image of the European Community (see chart):

In the autumn of 2014, 30 per cent of the British had a positive opinion of the EU, while 32 per cent viewed it negatively. In the EU countries as a whole, the ratio was 39 to 22 per cent.

British Prime Minister David Cameron, whose Conservative Party won the general election in May of 2015, is now even putting his country’s EU membership to the vote. As announced prior to the election, he wants to allow the British people to decide on the country’s continuance in the EU – perhaps as early as the autumn of 2016.

The outcome of the referendum cannot yet be predicted with certainty. What is clear, however, is that a withdrawal from the EU – the “Brexit” – would have serious repercussions for the British. Because, unless the EU makes the applicable concessions, the United Kingdom would no longer have unimpeded access to the Single European Market with its basic liberties:

- For example, without the freedom of movement for people and workers, it could become more difficult for British citizens to get jobs in other EU countries.

- The free movement of capital also would no longer be guaranteed. The British financial sector in particular has benefited from this liberty up to now; with a value added share of over 8 per cent, it represents a strong pillar of the economy in the UK.

Restrictions in the movement of capital could also prevent companies from other sectors in non-EU countries from making direct investments in the UK, since they could no longer use it as a springboard for expanding into the EU. US corporations in particular, who have heretofore used the UK as a toehold to the EU on account of the shared language, might now move their European branches to other locations in the EU. This involves quite a lot of capital: after all, between 2004 and 2013, the inventory of foreign direct investments in the UK increased by nearly 170 per cent to 975 billion pounds – which, at the current exchange rate, amounts to over 1,300 billion euros.

- The free movement of goods and services is also on the line. Both the UK and the EU could reintroduce customs duties; and the related clearance processes and other bureaucratic regulations would drive trade costs through the roof. The mutual recognition of national provisions would come to an end.

All of these factors would weaken cross-border trade – and the UK would not be the only country impacted:

In the year 2014, 48 per cent of the UK’s exported goods went to other EU countries – and 53 per cent of its imports were likewise from EU countries.

On balance, the imports from the EU exceeded the exports to the EU by 91 billion euros; in the trade of goods with Germany alone, the UK registered a trade deficit of more than 35 billion euros.

New trade hindrances would also do damage in the services sector; most recently, 37 per cent of all British service exports went to customers in other EU countries. In fact, the UK achieved a surplus of almost 20 billion euros in 2014.

These trade figures still do not entirely reflect the economic ties between the UK and the rest of the EU. It is also useful to take a closer look at the supply of intermediate goods – which can include raw materials and machine components, but also the rent of commercial real estate. These factors show how the value creation processes – in both the industrial and services sectors – are now structured across all of Europe.

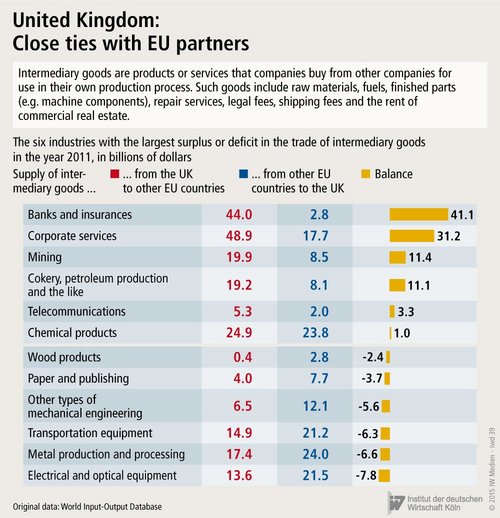

Of particular note is that, in certain industrial sectors, the UK is achieving a clear surplus in its trade of intermediate goods with other EU countries (see chart):

Most recently, the British financial sector’s supply of intermediate goods to the rest of the EU exceeded the corresponding imports by approximately 41 billion dollars. In the field of corporate services, the balance amounted to a good 31 billion dollars.

The British also came out ahead in its trade of intermediate goods in certain industrial sectors, such as the chemical and power industries.

A “Brexit” could impact the economic sectors in which the EU sees trade as being deficient, since other member states might be less likely to form applicable agreements that would hold open the door for British businesses to the Single European Market. In particular banks, consulting firms, energy suppliers and chemical companies from the UK would be most at risk of facing the resulting trade barriers.

Other British industries, such as the metal and electrical industry, would not suffer quite as strong an impact. After all, this is an industry in which the EU achieves surpluses in its trade of intermediary goods with the UK; hence, the remaining EU countries would not want to decrease their sales opportunities by creating any customs or trade hurdles.

More on the topic

Not so Different?: Dependency of the German and Italian Industry on China Intermediate Inputs

On average the German and Italian industry display a very similar intermediate input dependence on China, whether accounting for domestic inputs or not.

IW

China’s Trade Surplus – Implications for the World and for Europe

China’s merchandise trade surplus has reached an all-time high and is likely to rise further. A key driver appears to be a policy push to further bolster Chinese domestic manufacturing production, implying the danger of significant overcapacities.

IW